Day 7: Forest Bend (downstream from McCoy's Bridge) - Echuca

389 - 462 (73) km

|

| Forest Bend |

|

| The location of my campsite at Forest Bend relative to McCoy's Bridge (Murray Valley Highway). |

|

| Ready to go as the first sun of the day's sun-rays touch the river. |

|

| Perfect reflection in the stillness of the early morning. |

|

| Sunlight on the river. |

|

| As the river meanders through the landscape, I am alternately find myself hidden in sleepy shadows, or bathed in warm sunshine. |

The Goulburn is a quiet river. Except for the circus like excitement of the Lake Nagambie area, I saw very few people during the entire 462 km. Most days I would see one or two campers, fishermen enjoying the Goulburn's reputation for cod and yellow belly, or families sharing time in the bush together. Today was no different. The birds were my companions. Kingfishers whose silent flight along the river, flashes of blue and bobbing heads amongst the branches gave away their position. Ducks, leading me away from their nests before wheeling back kilometres later. Corellas and cockatoos feeding on the salt in the clay banks, small groups on low snags drinking from the water, or filling the trees on either side, and always the watchful sentries. Honeyeaters diving low, snapping insects, or bouncing off the water for a refreshing bath on the hot days. Willie wagtails battling with them for the best feeding sites. If honey-eaters, with their arrow like flight and powerful wing beats are the spitfires of the Redgum forests, willie wagtails are the helicopters, able to fly vertically and change direction in an instant. No insect can outfly them. Superb blue wrens, bravely declaring their territory from the tallest twig, despite their size. Tree creepers, the woodpeckers of the Australian bush, able to run vertical up a tree trunk in their search for insects hiding amongst the bark, but doing their best to hide on the side you are not with little sideways hops. As you progress down the Goulburn, the banks become taller and the river more sheltered, a true ribbon of life running through an increasingly dry environment.

An immature white bellied sea eagle watches me pass.

Typical campsite in the last section of the Lower Goulburn: a low sloping ledge with young grey box woodland above. In popular places, like this one, there may even be steps cut into the bank by previous campers.

Even though in most places the banks are steep, there are beautiful sandbars every now and then. As with other spots, the safest places to camp are usually a little bit back from the river (avoiding overhead branches).

Approaching the Murray there are signs of people enjoying the river. This homemade special demonstrates one of the things I like about the Goulburn: it is less flashy, there is less keeping up with the Joneses. You hardly find boats like this on the Murray anymore. In there place are $90,000 spaceship like craft with plush seats, stainless steel pontoons and aerodynamic sunshades. The builders of this boat didn't compromise on everything; it has a very impressive sound system.

Another good campsite.

Stewart's Bridge, just 4km from the confluence of the Goulburn and Murray Rivers.

Home built boats.

After 470km, at the point where the Goulburn spills into the Murray.

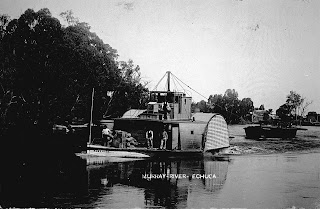

Approaching the junction with the Murray things began to change. With still 20 km to go, I could hear the high powered engines of large speed boats and as I rounded the last bend their wash, travelling up the Goulburn, met me like an incoming tide. Before I knew it, the current from the Goulburn swept me into the Murray and the swirling water where the two rivers meet. The Murray appeared wide and powerful, I felt like I was in a river estuary, experiencing a change of tide, being swept downwards to the sea. Gone was the intimacy of the Goulburn with its high banks and comparative isolation. The Murray was a hive of activity, experiencing the peak of its water skiing season. Gone was the idea that I could paddle wherever I liked, dodging snags and taking the course of my choice. With so much traffic, I followed the rules and stuck to the right; every river crossing a potentially dangerous situation. Most of the boats were of the largish kind; full of happy families, but producing a big wash. Such a wash is difficult in a smaller boat, but my sea kayak revelled in it, almost calling for more, ignoring its consequences for the banks. Bring it on! I had smelt home.

Back home in Echuca and wondering why I had never paddled the Goulburn before. I thoroughly recommend it. The Goulburn is a beautiful and isolated river. Set in the middle of Victoria, it is a touring paddler's dream.

The final 18 kilometres ticked away as if they were a walk in the park. I felt no tiredness, no pain. I knew every bend from here. I was home. What a great paddle. What a fantastic river. A hidden treasure. It has become part of my life.

Thanks for sharing it with me.